Finding Myself in the Wires

Tag: #editorial

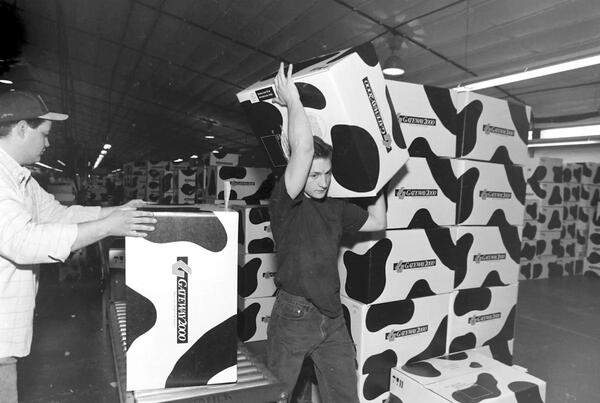

It will be a rare reader that does not remember the cow print boxes containing a lovingly packed Gateway 2000 PC and CRT display, but just in case:

My first computer didn't arrived in one of those. In fact, I don't recall it arriving in any box. My parents got it used from my cousin's much wealthier fiance that had just upgraded his home machine and no longer needed it. I had either just started high school or was about to, which was enough for them to finally purchase a family computer despite our constant financial troubles, though I have no idea how much they paid for it. I don't even remember the exact model, since those strings of numbers and letters were so esoteric to me at the time, but that beloved Gateway 2000 386/33C (I think?) became my first real window to the wider world of computing beyond what my old console video game systems could offer.

I'd say it turned out to be worth every penny.

With my memory recall being far from perfect, it's not likely that I have all the details about system specs and the time period correct. I know the computer was already behind in terms of graphical and processing power when it came into our home around '94 or '95. I think Gateway had already dropped the "2000" from their name by then, which dated my poor little machine even more. In an early taste of just how classist computer enthusiasts can be without realizing it, my friends poo-poo'd it with talk of their faster Pentiums and megahertz, lingo I would only come to understand much, much later because nobody seemed particularly interested in teaching me what it was all about. I just knew my machine was slower than what they were using, but it was my slow machine and I loved it.

The Gateway 386/33C could not run all the games I wanted to play, but there were still plenty that I look back fondly on, sometimes prompting me to blow the dust off and play today. With Windows 3.1 and DOS (version 5, maybe?), I still was able to build a respectable game library that included SimCity, a plethora of Sierra titles and Wolfenstein 3D. Being of more modest financial means, I also had special place in my heart for Microsoft's games, with Minesweeper and SkiFree being two time-wasting staples of my teen years. Their Flight Simulator series wouldn't enter my life until I had much better hardware, but that story is best saved for its own article.

Internet access was rammed through a 14.4k external modem that I think we got from a neighbor. We used the Compuserve and AOL floppies from the computer magazines I had spent all my chore money on and that was pretty amazing for all its clunky and noisy presentation of the world. But, for me, the real action was happening on BBSs, which a friend had introduced me to. That old Gateway 2000 could do some wild stuff, but dialing into someone else's computer and interacting with messages and files was akin to a drug for me. It felt subversive, somehow, like I was accessing a part of the Internet I was not supposed, some area reserved for social outcasts and people who knew how to peak beneath the surface of things. In retrospect, that feeling was probably inflated by the fact that I knew so little about computers at the time, but I was still more advanced in my use that my parents.

The subversiveness was admittedly an illusion of my own creation, bolstered by the newly popular film Hackers, hokey darling of the cyberpunk genre that it was, and many late nights spent reading William Gibson and Rudy Rucker novels. There was a seedy draw to the lifestyle portrayed in those stories, one that I both wanted to be part of and was also deeply afraid of getting lost in. This was at a stage in my life when I had no idea where I belonged and wanted nothing more than to escape from the awkward world of school and the perpetual dysfunction of home.

I mostly stuck to the local BBSs, largely due to the long-distance charges that could be accrued from the telecom companies at the time, but also because they tended to be smaller, so there was less waiting to dial in because the board's limited connections were all taken. Grandpa's Toolshed sticks out in my mind as one I frequently connected to, my memory telling me with some certainty that this was also the first place I downloaded the Anarchist's Cookbook, a popular counter-culture document at the time that turned out to be a lot of baloney, but the super-fun-to-think-about kind of baloney. There were other BBSs in my rotation, the names of which I only vaguely remember, like Teddy's Toy Box which seemed aimed at software cracking tools and distributing games, or Joker's, which I later found it was just one of many BBS's around the US and Canada of the same name but completely unrelated to each other.

It may have been Joker's BBS that hosted the annual barbecue that I attended twice, where my socially anxious teen self mostly just stood around listening to a bunch of crufty old nerds talk tech or bitch about the government while we ate burnt hot dogs and hockey puck burgers. Every second of it was glorious. As it turns out, the other users were mostly just people with boring jobs who liked technology. This was much easier to identify with than the mythos of these tech gurus I had built up in my head while reading their discussion about complex subjects I couldn't quite grasp, yet. While I didn't know as much about computers as these guys did, I wanted to, so we shared a lot of the same curiosities. It was probably about this time in my life that I learned the value of just shutting the futz up and observing for awhile, while noting where all your good resources were so they could be revisited later.

There is no story here of some magical mentor coming out of the woodwork to teach me the ways of the hacker, a term that really wasn't in any wide or serious use back then, despite the eponymous movie. I wish I had that story to tell, to be honest. Sometimes there was an individual that would show me a thing or two, but the reality is that I learned more from eavesdropping and reading message boards than anything. In any case, I did not consider myself a hacker. I still don't, but I suppose I've been called worse.

Keep in mind this was still very much what I call the RTFM glory days, where telling someone to read the futzing manual was actually not terrible advice, mostly because documentation for consumer-grade electronics was considerably more elucidated back then. In any case, I will also not identify as "self-taught," a phrase that I tend to associate with rugged individualists who have little to offer and too much to prove. There were plenty of times I would just read the instructions and try different things, just to see what happened, which is, in my very humble opinion, the root of the hacker mindset. The thing is, I would not have had anywhere to start had others not come along and written those instructions in the first place, so remembering those that walked the path before me served pretty well, even if I never met them.

Maybe this all happened during a fairly crucial period of cognitive development, being that I was about 16 or 17 by the time I started really hanging out with other computer geeks, but it shaped who I have become in a noticeable way. My resume states that one of my strengths is a love of figuring things out and that's probably the only statement on the whole document that hasn't been fuzzed a bit to look better for potential employers. Taking something apart so I can better understand it is not a fear that I have (although there are some reasonable limits to that) and I can be a little proud of that as it spills over into my non-technical life, resulting in periodic deconstruction of my own faults and biases or reinvention of myself as some new a curious appetite takes hold.

The mindset the little Gateway computer helped expose me to has resulted in a useful adaptability. Almost antithetical to that notion, I yearn for the days of the human-centric Internet, but not because I'm beating some drum about how much better things were "back then." It's more about looking critically at the modern Internet and just how far it has strayed from the path of being a tool of enrichment for the lives of anyone choosing to reach out and grasp it. What I feel when I look back is a abysmal sadness for the future we lost when we allowed corporate interests to take over the decision making process, guiding our technology away from making us smarter and into a reality where half of our population cannot tell the difference between a journalism and curated content. Perhaps it is not nostalgia itself that brings so many back into the vintage computing fold, but an attempt to recapture a hope we once felt, one that hinted at a slightly different Information Age where the users had all the power.

People must grow and our technology should facilitate that. Otherwise, what is the point?